The Food and Drug Administration approved a new gene therapy called Luxturna for the treatment of a rare, hereditary type of vision loss on Dec. 19, marking the first time therapy for a specific gene mutation has cleared the FDA’s approval process.

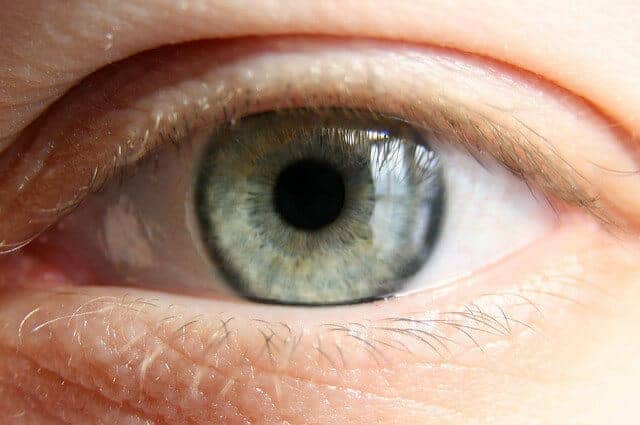

Produced by Spark Therapeutics, Luxturna is intended to treat a condition called biallelic RPE65 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy, which affects between 1,000 to 2,000 people in the U.S. and is marked by a progressive form of vision loss that often leads to blindness.

People with biallelic mutations have a defect in both copies of a specific gene in the retina. The newly approved gene therapy, which is administered by a surgeon, provides instructions to the faulty retinal genes, essentially casting off the defects and replacing them with healthy genes.

People with biallelic mutations have a defect in both copies of a specific gene in the retina. The newly approved gene therapy, which is administered by a surgeon, provides instructions to the faulty retinal genes, essentially casting off the defects and replacing them with healthy genes.

However, the price tag is expected to be astronomical. Experts believe the cost for the novel treatment may soar to $1 million or more. Despite the cost uncertainty, the new treatment may usher in a sweeping change to the way Americans and their physicians approach disease treatment.

“Today’s approval marks another first in the field of gene therapy – both in how the therapy works and in expanding the use of gene therapy beyond the treatment of cancer to the treatment of vision loss – and this milestone reinforces the potential of this breakthrough approach in treating a wide-range of challenging diseases,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D.

“The culmination of decades of research has resulted in three gene therapy approvals this year for patients with serious and rare diseases. I believe gene therapy will become a mainstay in treating, and maybe curing, many of our most devastating and intractable illnesses,” added Gottlieb.

Related: Breakthrough Gene-Editing Study Returns Sight to Blind Animals

Patients who opt for Luxturna will face two procedures – one for each eye – that take place at least six days apart, according to FDA drug information. The therapy is administered via injection, and patients will have to take immunosuppressant drugs following the procedures to make sure the body doesn’t have an adverse reaction.

The injection delivers a healthy copy of the RPE65 gene to the eye cells using a specifically engineered virus as the delivery mechanism. Once the healthy RPE65 gene reaches the retinal cells, it creates a normal protein that those with the genetic mutation can’t produce.

The new approval appears to be an early glimpse of more gene-based therapies hitting the U.S. marketplace, and the FDA said it will be adapting its policies to deal with the expected influx.

“We’re at a turning point when it comes to this novel form of therapy and at the FDA, we’re focused on establishing the right policy framework to capitalize on this scientific opening,” said Gottlieb.

“Next year, we’ll begin issuing a suite of disease-specific guidance documents on the development of specific gene therapy products to lay out modern and more efficient parameters – including new clinical measures – for the evaluation and review of gene therapy for different high-priority diseases where the platform is being targeted,” Gottlieb added.

Richard Scott is a health care reporter focusing on health policy and public health. Richard keeps tabs on national health trends from his Philadelphia location and is an active member of the Association of Health Care Journalists.

![How To: ‘Fix’ Crepey Skin [Watch]](https://cdn.vitalupdates.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/bhmdad.png)