Some cancer treatments may prove ineffective due to a surprising cause — bacteria living among cancer cells that disrupts drug therapy.

A new study from researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel discovered that a class of bacteria commonly found among pancreatic cancer cells mutes the effects of life-saving chemotherapy.

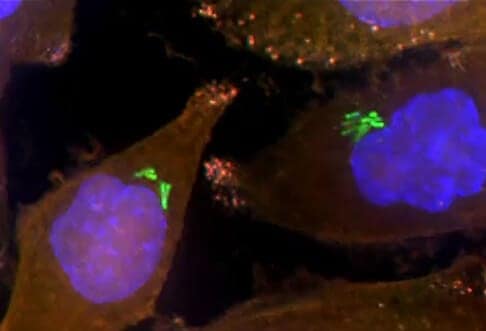

While many types of bacteria are essential to the body’s health, this class of bacteria certainly does not fit that category. With a close analysis of the interaction between the bacteria, which lives inside and among pancreatic cancer cells, and a chemotherapy drug called gemcitabine, the Weizmann researchers discovered that the bacteria metabolizes – or, essentially, eats – the drug, causing it to fail to treat the tumor.

“Because the topic is so new, we first used different methods to prove that there really were bacteria inside the tumors. Then we decided to look at the effect that these bacteria might have on chemotherapy,” said Dr. Ravid Straussman, a researcher with the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Molecular Cell Biology Department.

Related: Antibiotics Found to Counteract Benefits of Whole Grain Foods

Yet the groundbreaking discovery reveals that a simple intervention — the administration of antibiotics alongside chemotherapy — may reverse course and prevent the bacteria from interfering with drug therapy.

“A high percentage of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, a tumor type commonly treated with gemcitabine, contain the culprit bacteria,” report the researchers in the journal Science. “These correlative results raise the tantalizing possibility that the efficacy of an existing therapy for this lethal cancer might be improved by cotreatment with antibiotics.”

Baffling Bacteria

To study how bacteria interferes with chemotherapy, the researchers isolated bacteria cultures taken from patients’ pancreatic cancer cells and then mixed the bacteria with gemcitabine. They pinpointed a specific gene — called cytidine deaminase (CDD) — that appears in two forms, long or short. Only bacteria with a long form of CDD were able to interfere with the cancer drug.

The researchers then tested their findings in mouse studies. They discovered that only long-form bacteria was resistant to therapy, while bacteria that had the CDD gene disabled was not. Also, they found that after giving the mice antibiotics, their bodies showed no resistance to the chemotherapy.

While the researchers note that many questions remain, they believe their work takes an important step forward in understanding cancer treatment and the role of organisms previously not understood.

Related: Chemotherapy May Make Cancer More Likely to Spread

Ultimately, the research adds to the “growing evidence … that microbes can influence the efficacy of cancer therapies,” report the study authors.

Other cancer studies that have appeared in recent years have touted the positive effects of bacteria. For instance, a 2016 study appearing in Science Translational Medicine found that scientists could engineer certain strains of bacteria to invade and kill networks of cancer cells. Another study from MIT researchers found that scientists could harness bacteria to deliver “toxic payloads” to cancer cells.

In that study, the researchers noted that tumors are something of a breeding ground for bacteria to flourish. While those studies approach bacteria from a different angle, they all shed light on an area of importance for how the medical community understands cancer.

Richard Scott is a health care reporter focusing on health policy and public health. Richard keeps tabs on national health trends from his Philadelphia location and is an active member of the Association of Health Care Journalists.

![How To: ‘Fix’ Crepey Skin [Watch]](https://cdn.vitalupdates.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/bhmdad.png)